Trafficking Routes

last updated April 2019

Trafficking in persons is not limited to specific countries or regions. According to the International Organization for Migration (IOM), human trafficking victims representing 169 different nationalities were identified in 172 countries worldwide.[1] Between 2010 and 2012, U.N. Office on Drugs and Crime also identified approximately 510 distinct human trafficking flows.[2] Although trafficking occurs worldwide, trafficking patterns and volumes may vary in different parts of the world.

Organizations that study trafficking patterns tend to classify countries as source or origin countries, transit countries or destination countries. However, this classification system can be misleading because many countries fall under each of these categories at some point.[3] Additionally, the UNODC has pointed out that trafficking flows are dominated less by clear geographic boundaries than by relative pockets of economic disparity, with victims flowing from poorer to richer areas within countries, regions or across the globe.[4]

In simple terms, a source or origin country is a country where traffickers commonly find and recruit women and girls for their operations. Once traffickers have recruited an individual, that person is moved through intermediary or transit countries, sometimes for extended periods during which the women may be forced into labor or the sex trade. Transit countries are chosen for the geographical location and are usually characterized by weak border controls, proximity to destination countries, corruption of immigration officials, or affiliation with organized crime groups that are involved in trafficking. In general, “organized criminals will try to push people over any border that is easiest for them to cross.”[5] Destination countries are the last link in the human trafficking chain. These countries receive trafficking victims and are generally more economically prosperous than origin countries. Destination countries can support a large commercial sex industry or a forced labor industry, the modern equivalent of slavery. The financial return to traffickers per victim is also highest in richer countries.

Additionally, victims are most commonly trafficked within their home country or region of origin.[6] For example, in North Africa, over 80% of detected trafficking victims were trafficked domestically.[7] Further, in Eastern Europe and Central Asia, 100% of detected trafficking victims were trafficked within the same subregion, a statistic closely followed by South Asia (99%), Sub-Saharan Africa (99%), East Asia and the Pacific (97%), and South America (93%).[8]

Trafficking flows share certain similar traits no matter where they are found in the world. Certain dimensions of development in a given country have a direct effect on the likelihood of human trafficking within that country’s borders. For example, poverty is one of the prime risk factors associated with human trafficking. When combined with other risk factors such as limited economic or educational opportunity, poor governance, weakened rule of law in post-conflict countries, and natural disaster, the conditions in a country become ripe for the exploitative practices of human traffickers. International destinations for trafficking most often include well-developed, wealthy and industrialized areas of the world. As stated by the UNODC in 2014,

The ‘global north’ attracts victims from all over the world. Traffickers in poorer countries have an economic interest of moving victims there – to Western Europe, North America or the Middle East – while there is little to gain from moving victims in the opposite direction. In addition to economic factors, there are also other conditions that have an impact on the directions of trafficking flows. These include issues related to job markets, migration policy, regulation, prostitution policy, legal context and law enforcement and border control efficiency . . . . [T]o traffic victims internationally is complicated and may involve significant risks . . . Relatively few traffickers are able to organize themselves well enough to conduct effective transregional trafficking activities.[9]

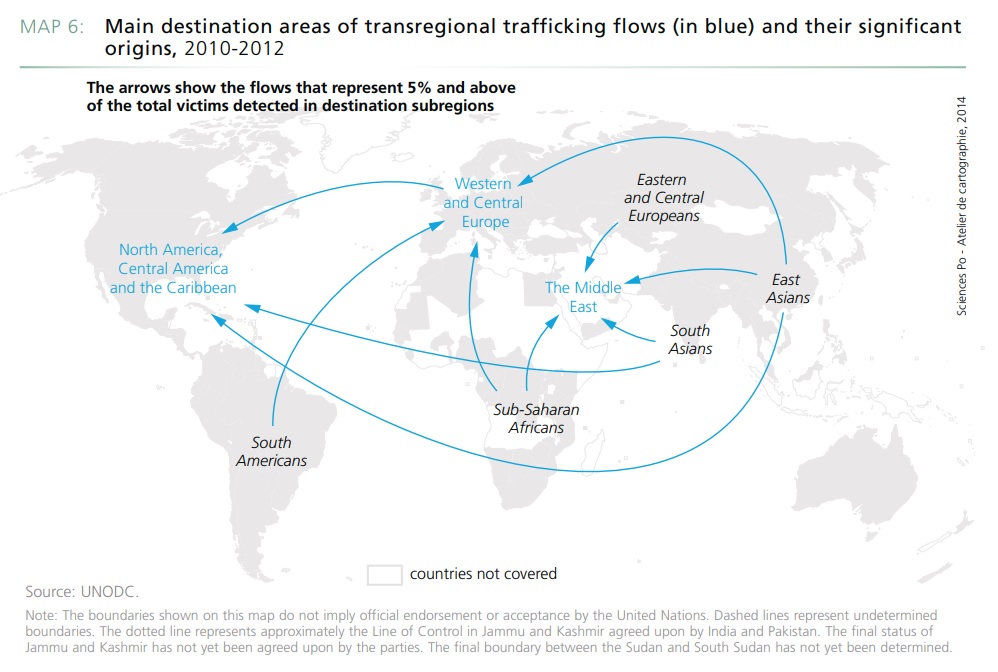

Analyzing and tracking human trafficking flows or routes is a difficult task given the still hidden nature of the crime and because traffickers regularly shift routes to avoid detection. In its 2016 Global Trafficking report, the UNODC noted that, “the available data is insufficient to delineate trafficking routes.”[10] However, some work has been done to identify general flows, and the UNODC includes maps of major trafficking flows in its 2014 Global Report, such as this one depicting transregional trafficking flows:

Source, United Nations Office on Drugs and Crime, 2014[11]

As noted by one commentator in the European Journal of Criminology, “[t]he lack of certainty about the legal responsibilities of origin, transit and destination countries helps traffickers continue to operate with impunity.”[12] For this reason, it is vital that origin, transit and destination countries cooperate and develop joint strategies to combat trafficking. According to the U.S. Department of State, “[d]estination countries must work with transit and source countries to stem the flow of trafficking; source countries must work not only to prevent trafficking, but to help with the reintegration of trafficking victims back into their home societies.”[13]

[1] United Nations Office on Drugs and Crime, Global Report on Trafficking in Persons 47 (2018) [hereinafter 2018 Global Report].

[2] United Nations Office on Drugs and Crime, Global Report on Trafficking in Persons 5 (2014) [hereinafter 2014 Global Report].

[3] United Nations Office on Drugs and Crime, Global Report on Trafficking in Persons 40 (2016) [hereinafter 2016 Global Report].

[4] UNODC, 2018 Global Report 9.

[5] Vesna Nikolic-Ristanovic, et al., Organization for Security and Co-Operation in Europe, Trafficking in People in Serbia 161 (2004).

[6] UNODC, 2018 Global Report 9, 23.

[7] Id.at 87.

[8] Id. at 9.

[9] UNODC, 2014 Global Report 48.

[10] UNODC, 2016 Global Report 40.

[11] UNODC, 2014 Global Report 40.

[12] Benjamin Perrin, Just Passing Through? International Legal Obligations and Policies of Transit Countries in Combating Trafficking in Persons, 7 European J. Criminology 11, 15 (2010) (citing M.A. Clark, Trafficking in Persons: An Issue of Human Security, 4 J. Human Development 247 (2003).

[13] U.S. Department of State, Victims of Trafficking and Violence Protection Act of 2000: Trafficking in Persons Report 5 (2002).